Waitlists lie

Why enthusiastic feedback means nothing if they're spending $0 on the problem today.

Hundred waitlist signups feels like validation. It’s not. It’s a permission slip to waste three months of runway.

I learned this the expensive way. I still remember my first start up, because this lesson burned itself into my emotional memory.

We had enthusiastic users who promised they’d buy the moment we launched. Sarah, a director at a mid-market SaaS company, told us our solution would “change everything” for her team. She signed our waitlist. She introduced us to her colleagues. She gave us detailed feedback on mockups. When we launched three months later, she went silent. Not because the product was wrong—because signing a waitlist costs nothing and buying requires budget authority, procurement approval, and organizational priority.

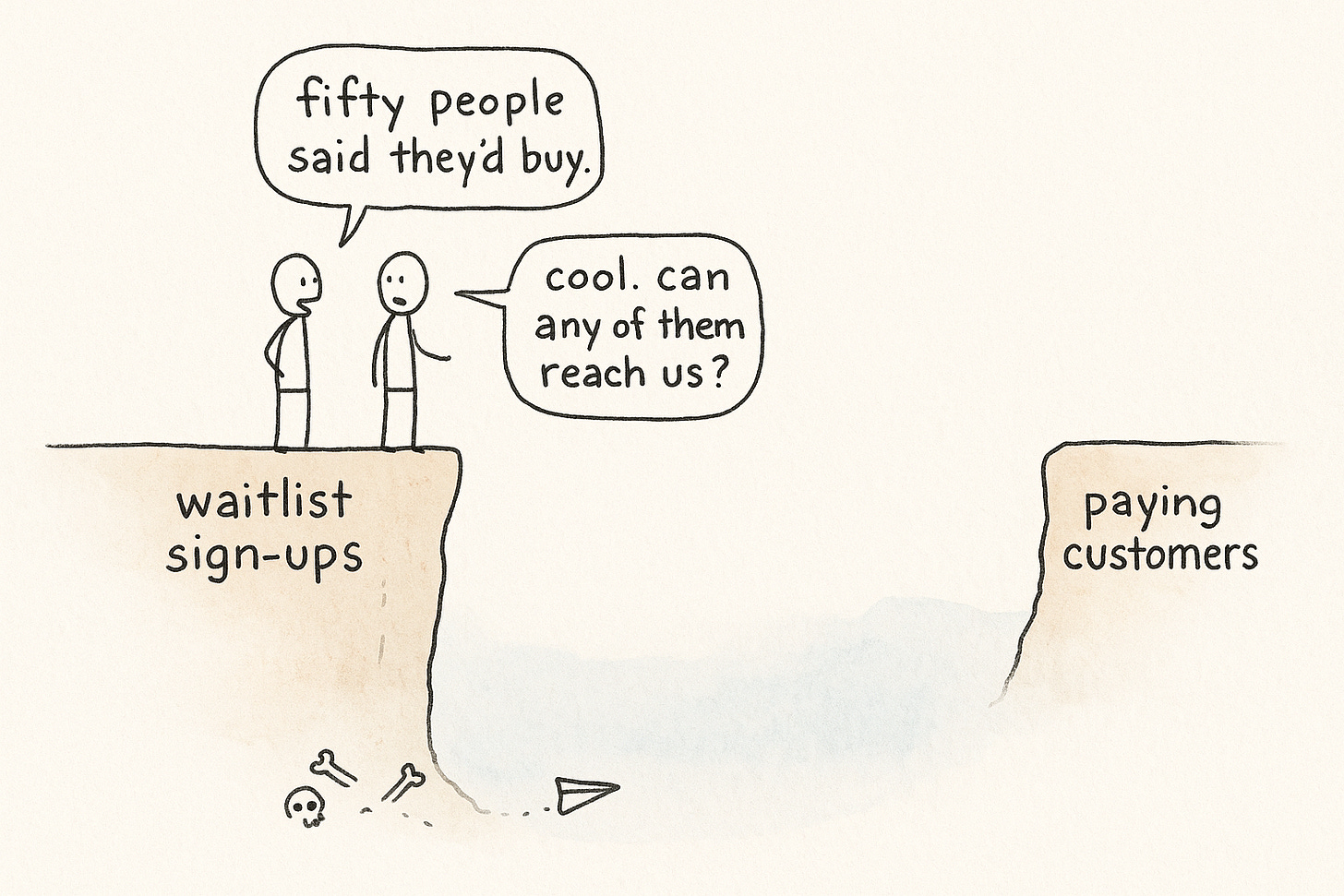

The gap between “I’d use this” and “Here’s my credit card” is a chasm filled with the corpses of well-validated products. My product became one of them.

Here’s what actually happened: We spent three months and $50,000 building for people who, when I finally asked them point-blank, were spending exactly $0 on the problem we were solving. Zero budget. Zero headcount. Zero tools. Just complaints and wishful thinking about how nice it would be if someone else fixed their workflow.

The most dangerous validation question isn’t “Would you use this?”—it’s never asking “What are you spending your budget on right now?” That question would have saved us. Instead, we validated desire and completely missed budget priority. We built for enthusiastic complainers instead of desperate buyers.

Here’s what to actually look for when someone says they love your idea.

Why waitlists lie

Signing up for a waitlist costs nothing—no budget discussion, no procurement, no org chart navigation, no career risk. It’s the professional equivalent of liking a friend’s startup on social media. It feels supportive in the moment and requires zero commitment.

Buying, on the other hand, requires everything a waitlist doesn’t: budget authority, stakeholder buy-in, competitive evaluation, implementation timeline, success metrics, career risk if it fails. The gap between these two actions is enormous, but most founders treat them as the same thing.

The Lean Startup methodology tells you to “get out of the building” and talk to customers. Running Lean walks you through problem interviews and solution validation. Both are good advice—as far as they go. But they stop exactly one question short of where they need to go. They teach you to validate that people have the problem and like your solution. They don’t teach you to validate that people are bleeding enough to write a check.

What existing spend reveals

When Uber was validating their idea, they didn’t ask “Would you use a ride-sharing app?” They tracked how much their target users were spending on taxis and black cars. $20-40 per ride, multiple times per week, thousands of dollars per year—that’s existing spend. That’s a real budget with real pain.

Same with Slack—they didn’t ask “Would you pay for better team communication?” They looked at companies drowning in email and scattered across five different tools, each with its own subscription and admin overhead.

Airbnb didn’t validate “Would you stay in someone’s house?”—they validated “What are you spending on hotels?” The answer: $150-300 per night in the cities they were targeting, billions in annual hotel revenue up for grabs. That’s not hypothetical willingness—that’s revealed preference.

Eric Ries validated Dropbox with a demo video that got 75,000 signups. Great marketing, but here’s what matters: The reason Dropbox worked wasn’t the waitlist—it was that people were already paying for worse file-sharing solutions. They had existing spend to reallocate.

None of these companies validated desire. They validated existing spend. But most validation frameworks never teach you to look for that.

The problem with customer development frameworks is they optimize for customer enthusiasm, not customer economics. Steve Blank’s Customer Development teaches you to find customers who have the problem. The Lean Canvas walks you through validating the problem exists. Y Combinator’s advice is to “make something people want.”

All true. All insufficient.

Because the question isn’t “Do people want this?” The question is “What are people already spending on this?” Desire is cheap. Revealed preference is expensive. And only expensive counts.

One question

After Sarah, I changed my entire validation approach. My first call with the next prospect—let’s call him Michael, VP of Procurement at a Series B company—started the same way. He described his pain point, agreed our solution would help, got excited about the demo.

Then I asked: “Walk me through how you’re handling this today. What tools are you using? How much do they cost? How much time does your team spend on workarounds?”

Michael pulled up his budget spreadsheet mid-call. “We’re spending about $8K/month on three different tools that partially solve this, plus probably 20 hours a week of engineering time on manual processes. Call it $150K/year all in.”

Then he asked about our pricing—before I’d even finished the demo. We signed him six weeks later.

Then there was Lisa. VP at a Fortune 500. Zero budget allocated. I almost wrote her off. But when I asked what they were spending, she said “Nothing officially. But last quarter my team hired 4 working students to do that stuff manually. It’s a pain and we’re still not seeing the results. I can’t put on a budget line but it is bleeding us.” We signed her eight weeks later after she got temporal budget approval.

The question isn’t “Would you use this?” The question is: “What are you spending on this problem right now—in money and in time?”

Not “what would you pay?” Not “is this valuable?” Not “would this make your life easier?” Those questions get you enthusiasm. The spending question gets you economics.

Don’t interrogate. Just ask: “Walk me through how you’re handling this today—what tools, what time, what cost?” Then shut up and listen.

Smart founders who’ve learned this lesson ask about spend in the first conversation. Inexperienced founders wait until they’ve built the product. The difference is three months of runway.

There’s a reason VCs ask about your first ten customers’ buying process—they know that most founders can describe their product features in detail but can’t tell you what budget line item their customers used to buy it. The founders who can answer that question are the ones who identified real buyers early. The founders who can’t are still talking to Sarahs.

So what?

The hardest part isn’t asking the question. The hardest part is what you do with the answer.

When someone enthusiastically tells you they love your solution but admits they’re spending $0 on the problem, every founder instinct screams “But they really need this! I just need to educate them!” That instinct is wrong. They don’t need it enough to prioritize it. And you can’t create urgency where economics don’t exist.

Sarah emailed me for months after. Each time, she mentioned the workflow is still painful. Each time, she’d still spent $0 to fix it. That’s how you know it was never real.

The gap between “I love this” and “Here’s my credit card” isn’t a gap in your product. It’s a gap in their urgency. And you can’t build your way across it.